Bantu languages

| Bantu | |

|---|---|

| Geographic distribution: |

Subsaharan Africa, mostly Southern Hemisphere |

| Linguistic Classification: | Niger-Congo Atlantic-Congo Benue-Congo Bantoid Southern Bantoid Bantu |

| Subdivisions: |

Northeast Bantu

Southern Bantu

Zones A–S (geographic)

Central Bantu (dubious)

Northwest Bantu (dubious)

|

| ISO 639-2 and 639-5: | bnt |

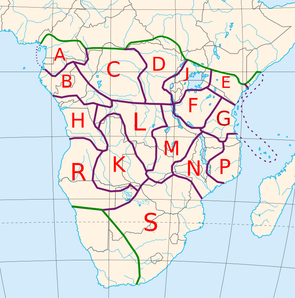

Map showing the approximate distribution of Bantu vs. other Niger-Congo languages. |

|

The Bantu languages (technically Narrow Bantu languages) constitute a sub-branch of the Niger-Congo languages. By one estimate, there are 522 languages in the Bantu family, 668 languages in the Southern Bantoid branch which includes Bantu, and 1,532 in Niger-Congo.[1] Bantu languages are spoken largely east and south of the present day country of Cameroon; i.e., in the regions commonly known as central Africa, east Africa, and southern Africa. Parts of the Bantu area include languages from other language families (see map).

The Bantu language with the largest total number of speakers is Swahili.

According to Ethnologue [2] the Bantu language with the largest number of speakers as a first language is Shona with 10.8 million speakers in Zimbabwe. Zulu comes second with 10.3 million speakers. Ethnologue lists Manyika and Ndau as separate languages, though Shona speakers consider them to be two of the five main dialects of Shona. If the 3 million Manyika and Ndau speakers are included among the Shona, then Shona totals 13.8 million first-language speakers.

The Bantu languages originated in the region of eastern Nigeria or Cameroon. About 2000 years ago the Bantu people spread southwards and eastwards, introducing agriculture and iron working and colonizing much of the continent in the Bantu expansion.

The technical term Bantu, simply meaning "people", was first used by Wilhelm Heinrich Immanuel Bleek (1827-1875) as this is reflected in many of the languages of this group. A common characteristic of Bantu languages is that they use words such as muntu or mutu for "person", and the plural prefix for human nouns starting with mu- (class 1) in most languages is ba- (class 2), thus giving bantu for "people". Bleek, and later Carl Meinhof, pursued extensive studies comparing the grammatical structures of Bantu languages.

Contents |

Classification

The term 'narrow Bantu' was coined by the Benue-Congo Working Group to distinguish Bantu as recognized by Malcolm Guthrie in his seminal 1948 classification of the Bantu languages from Bantoid languages not recognized as Bantu by Guthrie (1948). In recent times, the distinctness of Narrow Bantu as opposed to the other Southern Bantoid groups has been called into doubt (cf. Piron 1995), but the term is still widely used.

There is no genealogical classification of the (Narrow) Bantu languages. The most widely used system, the alphanumeric coding system developed by Guthrie, is mainly geographic. However, based on reflexes of proto-Bantu tone patterns, zones A–C and part of D are grouped together as Northwest Bantu, and zones D–S as Central Bantu. Northwest Bantu is more divergent internally than Central Bantu, and perhaps less conservative due to contact with non-Bantu Niger-Congo languages; however, Central Bantu is likely the innovative line cladistically, with Northwest being the non-Central languages, not a family in their own right.

The only attempt at a detailed genetic classification to replace the Guthrie system is the 1999 "Tervuren" proposal of Bastin, Coupez, and Mann.[3] However, it relies on lexicostatistics, an inferior methodology. Meanwhile, Ethnologue has added languages to the Guthrie classification that Guthrie overlooked, while removing the Mbam languages (much of zone A), and shifting some languages between groups (much of zones D and E to a new zone J, for example, and part of zone L to K, and part of M to F) in an apparent effort at a semi-genetic, or at least semi-areal, classification. However, zone S (Southern Bantu) does appear to be a coherent group. The languages which share Dahl's Law may also form a valid group, Northeast Bantu. The development of a rigorous genealogical classification of many subdivisions of Niger-Congo, not just Bantu, is hampered by insufficient data.

Language structure

Guthrie reconstructed both the phonemic inventory and the core vocabulary of Proto-Bantu.

The most prominent grammatical characteristic of Bantu languages is the extensive use of affixes (see Sesotho grammar and Luganda language for detailed discussions of these affixes). Each noun belongs to a class, and each language may have several numbered classes, somewhat like genders in European languages. The class is indicated by a prefix that's part of the noun, as well as agreement markers on verb and qualificative roots connected with the noun. Plural is indicated by a change of class, with a resulting change of prefix.

The verb has a number of prefixes. In Swahili, for example, Mtoto mdogo amekisoma, (also Kamwana kadoko kariverenga in Shona language) means 'The small child has read it [a book]'. Mtoto 'child' governs the adjective prefix m- and the verb subject prefix a-. Then comes perfect tense -me- and an object marker -ki- agreeing with implicit kitabu 'book'. Pluralizing to 'children' gives Watoto wadogo wamekisoma (Vana vadoko variverenga in Shona), and pluralizing to 'books' (vitabu) gives Watoto wadogo wamevisoma.

Bantu words are typically made up of open syllables of the type CV (consonant-vowel) with most languages having syllables exclusively of this type. The morphological shape of Bantu words is typically CV, VCV, CVCV, VCVCV, etc; that is, any combination of CV (with possibly a V- syllable at the start). In other words, a strong claim for this language family is that almost all words end in a vowel, precisely because closed syllables (CVC) are not permissible. This tendency to avoid consonant clusters is important when words are imported from English or other non-Bantu languages. An example from Chichewa: the word "school", borrowed from English, and then transformed to fit the sound patterns of this language, is sukulu. That is, sk- has been broken up by inserting an epenthetic -u-; -u has also been added at the end of the word. Another example is buledi for "bread". Similar effects are seen in loanwords for other non-African CV languages like Japanese.

Reduplication

Reduplication is a common morphological phenomenon in Bantu languages and is usually used to indicate frequency or intensity of the action signalled by the (unreduplicated) verb stem [3]

- Example: in Swahili piga means "strike", pigapiga means "strike repeatedly".

Well-known words and names that have reduplication include

- Bafana Bafana

- Chipolopolo

- Eric Djemba-Djemba

- Lualua

- Ngorongoro

- Polepole (Swahili for slowly, or slowly-slowly). - In swahili pole means sorry, to express sympathy.

- Haraka-haraka (Swahili for quickly, or quickly-quickly, compare with vite-vite in French, that has the approximate meaning to 'fast-fast' in English).

Repetition emphasizes the repeated word in the context that it is used. For instance, "Mwenda pole hajikwai," while, "Pole pole ndio mwendo," has two to emphasize the consistency of slowness of the pace. The meaning of the former in translation is, "He who goes slowly doesn't trip," and that of the latter is, "A slow but steady pace wins the race." Haraka haraka would mean hurrying just for the sake of hurrying, reckless hurry, as in "Njoo! Haraka haraka" [come here! Hurry, hurry].

On the contrary to the above definition, there are some words in some of the languages in which reduplication has the opposite meaning. It usually denotes short durations, and or lower intensity of the action and also means a few repetitions or a little bit more.

- Example 1: in isiZulu and SiSwati hamba means "go", hambahamba means "go-go meaning go a little bit, but not much".

- Example 2: in both of the above languages shaya means "strike", shayashaya means "strike-strike, meaning strike a few more times lightly, but not heavy strikes and not too many times"

Notable Bantu languages

Following are the principal Bantu languages of each country.[4] These are those languages with at least 10% the number of speakers of the main Bantu language in the country, as long as that constitutes at least 1% of the population.

Most languages are best known in English without the class prefix (Swahili, Tswana, Ndebele), but are sometimes seen with the (language-specific) prefix (Kiswahili, Setswana, Sindebele). In a few cases prefixes are used to distinguish languages with the same root in their name, such as Tshiluba and Kiluba (both Luba), Umbundu and Kimbundu (both Mbundu). The bare (prefixless) form typically does not occur in the language itself, but is the basis for other words based on the ethnicity. So, in the country of Botswana the people are the Batswana, one person is a Motswana, and the language is Setswana; and in Uganda, centered on the kingdom of Buganda, the dominant ethnicity are the Baganda (sg. Muganda), whose language is Luganda.

Angola

Botswana

Burundi

Cameroon

Central African Republic

Democratic Republic of the Congo (Congo-Kinshasa)

Equatorial Guinea

Kenya

Lesotho Malawi

Mozambique

Namibia

|

Republic of the Congo (Congo-Brazzaville)

Rwanda

South Africa

Swaziland

Tanzania

Uganda

Zambia

Zimbabwe

|

Bantu words popularised in western cultures

Some words from various Bantu languages have been borrowed into western languages. These include:

- Bongos

- Bomba

- Bwana

- Candombe

- Conga

- Gumbo

- Hakuna matata

- Jenga

- Jumbo

- Kalimba

- Kwanzaa

- Mambo

- Mbira

- Marimba

- Rumba

- Safari

- Samba

- Simba

- Ubuntu

Other relevant links

- Malcolm Guthrie

- Meeussen's rule

- Noun class

- Bantu peoples

- Guthrie classification of Bantu languages

Bibliography

- Guthrie, Malcolm. 1948. The classification of the Bantu languages. London: Oxford University Press for the International African Institute.

- Guthrie, Malcolm. 1971. Comparative Bantu, Vol 2. Farnborough: Gregg International.

- Heine, Bernd. 1973. Zur genetische Gliederung der Bantu-Sprachen. Afrika und Übersee, 56: 164–185.

- Maho, Jouni F. 2001. The Bantu area: (towards clearing up) a mess. Africa & Asia, 1:40–49.

- Maho, Jouni F. 2002. Bantu lineup: comparative overview of three Bantu classifications. Göteborg University: Department of Oriental and African Languages.

- Piron, Pascale. 1995. Identification lexicostatistique des groupes Bantoïdes stables. Journal of West African Languages, 25(2): 3–39.

References

External links

- Comparative Bantu Online Dictionary - includes a comprehensive bibliography.

- Bantu online resources by Jacky Maniacky, including

- Contini-Morava, Ellen. Noun Classification in Swahili. 1994.

- List of Bantu language names with synonyms ordered by Guthrie number.

- Introduction to the languages of South Africa

- Etymology Dictionary

- Adaptation of English loanwords in Chichewa

- Bemba Phonology

- Journal of West African Languages: Narrow Bantu

- Bantu Languages of Uganda